The thirtieth UN climate conference in Belém, Brazil, concluded with developed nations committing to triple climate adaptation finance for vulnerable countries by 2035, while systematically avoiding binding language on fossil fuel reduction that over 80 nations demanded. This outcome crystallizes a pattern emerging across recent COP gatherings: financial mechanisms advance incrementally while decarbonization timelines remain deliberately ambiguous, creating a structural disconnect between stated temperature targets and enforceable transition pathways.

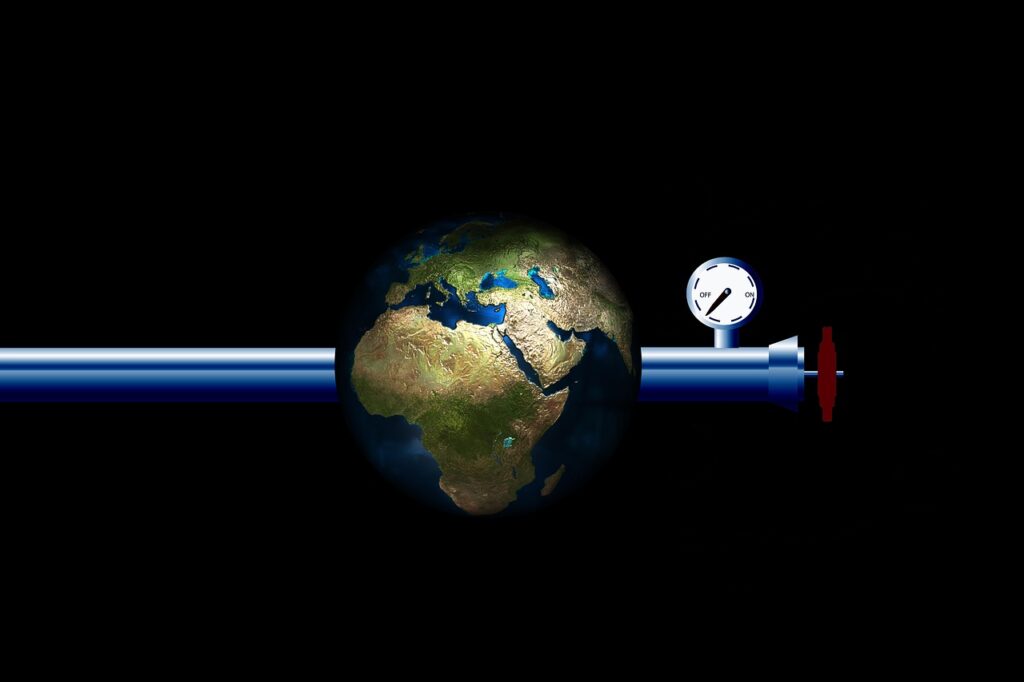

The final agreement text omits explicit references to coal, oil, or natural gas phasedown commitments, despite coalition pressure from Colombia, Germany, Kenya, and similar economies seeking concrete transition obligations. Energy exporter nations and diplomatic resistance diluted language that might have established measurable fossil fuel reduction targets, repeating negotiation dynamics visible at previous conferences where hydrocarbon-dependent economies leverage consensus requirements to block binding commitments. The absence of transition specificity matters considerably more than rhetorical affirmations of the 1.5°C Paris Agreement threshold, which the text reconfirms without accompanying enforcement architecture.

Financial commitments represent the conference’s tangible progress metric. Tripling existing adaptation support addresses immediate vulnerability in nations facing intensifying drought cycles, flood frequency increases, and heat wave mortality without contributing to historically significant emissions. However, the agreement structure provides no verification mechanism ensuring funds reach intended recipients or achieve stated adaptation objectives. The framework establishes financial flows without corresponding accountability for expenditure effectiveness or climate outcome improvements, creating potential for capital deployment that satisfies political commitments without delivering proportional resilience gains.

Brazil’s non-binding proposals on just transition from fossil fuels and forest protection operate through voluntary state participation rather than treaty obligations. This voluntary architecture reflects negotiation realities where binding commitments prove politically unattainable, but it also removes consequences for non-compliance. States can signal alignment with transition principles without restructuring domestic energy policies or facing diplomatic repercussions for maintaining fossil fuel subsidies and exploration licensing. The practical impact of voluntary frameworks depends entirely on whether major emitters adopt corresponding domestic legislation, which COP processes cannot compel.

The coalition of 80-plus nations, including the European Union and member states, launching a Brazil-led fossil fuel transition partnership, represents organizational progress on parallel tracks outside formal COP agreements. This formation acknowledges that consensus-based treaty negotiations cannot produce the transition speed required by atmospheric carbon budgets, necessitating voluntary coalitions willing to implement faster timelines. The partnership emphasizes human rights protection, labor rights preservation, gender equity and stakeholder inclusion during energy transitions, addressing social dimensions often marginalized in technical decarbonization discussions.

EU positioning at COP30 combined defense of Paris Agreement frameworks with acknowledgment that current measures remain insufficient. The bloc advocated for explicit fossil fuel phasedown language and accelerated clean energy deployment timelines, achieving partial incorporation of these priorities into the final text. EU negotiators secured language confirming the necessity of limiting temperature increases to 1.5°C and encouraging fossil fuel transition, but without the binding commitments or implementation timelines the bloc publicly sought. This outcome positions the EU as maintaining climate leadership rhetoric while accepting negotiated compromises that dilute enforceability.

The European Union’s independent commitments, established at the Dubai and Baku conferences, include progressive fossil fuel elimination, tripling renewable energy installed capacity, and doubling energy efficiency improvement rates by 2030. These unilateral pledges operate regardless of broader international agreement, signaling that leading economies will implement transition policies through domestic and regional mechanisms rather than waiting for global consensus. Whether this fragmented approach delivers sufficient aggregate emissions reductions depends on coordination between major economies and technology transfer effectiveness to emerging markets.

Temperature target maintenance at 1.5°C without corresponding fossil fuel reduction mandates exposes the enforcement vacuum central to COP limitations. Scientific assessments indicate current emissions trajectories exceed carbon budgets compatible with 1.5°C warming limits, meaning the target faces probable breach within years absent immediate, sustained emissions reductions. Reaffirming the target without implementation mechanisms converts it from an operational constraint to an aspirational reference point, maintaining diplomatic consensus while permitting continued policy-reality divergence.

States accepted obligations to submit regular progress reports on implemented measures, but without rigorous international oversight or compliance penalties. This self-reporting framework enables selective disclosure, optimistic projections, and accounting methodologies that obscure actual emissions trends. The absence of independent verification or consequences for underperformance transforms reporting requirements into bureaucratic exercises rather than accountability tools. Previous COP cycles demonstrate that voluntary reporting without enforcement produces highly variable data quality and limited policy adjustments when nations fall short of commitments.

The tripling of adaptation finance, while representing quantified progress, operates within development assistance frameworks historically marked by delivery shortfalls and implementation delays. Developed nations previously committed to mobilizing $100 billion annually by 2020 for climate action in developing countries, a target reached only in 2022 after years of underdelivery. The new tripling commitment by 2035 extends timelines without addressing structural issues in climate finance architecture: slow disbursement processes, project approval bottlenecks, and persistent gaps between pledged and delivered funds.

Adaptation finance requirements for vulnerable nations continue escalating as climate impacts intensify beyond projections underlying earlier assessments. Small island states facing existential threats from sea level rise, Sahel nations experiencing desertification acceleration, and South Asian countries managing monsoon pattern disruption require adaptation investments exceeding current pledges by substantial margins. The gap between available finance and actual adaptation costs widens annually as physical climate risks compound, meaning tripled funding addresses only portions of genuine requirements rather than closing vulnerability gaps.

Forest protection proposals in Brazil advanced at COP30, confronting implementation challenges visible in the country’s own Amazon conservation record. Despite rhetoric emphasizing forest preservation, Brazil’s deforestation rates fluctuate with political leadership changes and enforcement resource allocation. Non-binding international forest protection agreements depend on domestic political will, maintaining consistent priorities across election cycles and economic pressures, conditions rarely sustained long-term. Monitoring technologies, including satellite surveillance, provide deforestation detection capabilities, but translating detection into effective intervention requires governance capacity and economic alternatives for forest-dependent communities.

The repeated pattern of COP conferences producing financial commitments while deferring fossil fuel transition timelines reflects negotiating dynamics where economic disruption fears override climate urgency among key players. Major fossil fuel producers and industrial economies dependent on hydrocarbon revenues resist binding phasedown language, leveraging consensus requirements to dilute text. Meanwhile, climate-vulnerable nations prioritize adaptation finance for immediate threats over long-term mitigation commitments that they lack the capacity to implement. This divergence produces agreements addressing symptoms through financial transfers while avoiding root cause interventions in energy systems.

Latin American nations expressing disappointment with fossil fuel language omissions face internal contradictions between climate advocacy and resource extraction dependencies. Several countries in the region maintain aggressive oil and gas exploration programs while simultaneously calling for global fossil fuel reduction, reflecting tension between climate positioning and fiscal realities. Brazil’s Petrobras continues deepwater exploration despite government climate commitments, Colombia expands coal exports while advocating phasedowns, and similar patterns appear across the region. These contradictions limit negotiating credibility and complicate coalition formation around binding commitments that nations themselves cannot meet.

Scientific community reactions to COP30 outcomes emphasize the widening gap between negotiated agreements and emissions pathways compatible with stated temperature targets. Climate models indicate that maintaining fossil fuel consumption near current levels through 2030 makes 1.5°C exceedance virtually certain regardless of subsequent reduction efforts, due to cumulative emissions and inertia in energy systems. The conference’s avoidance of near-term fossil fuel reduction targets therefore conflicts fundamentally with atmospheric physics constraints, creating policy trajectories misaligned with stated objectives.

The triennial reporting obligations state accepted provide measurement points for tracking progress, but without interim targets or corrective mechanisms when nations underperform. This structure enables perpetual target extension: when 2028 reports show insufficient progress toward 2030 goals, negotiations can establish new 2035 targets without addressing systemic implementation failures. The cycle of target-setting followed by shortfall recognition followed by new target establishment has characterized climate negotiations for decades, producing limited acceleration in actual emissions reductions despite increasingly urgent rhetoric.

Partnership initiatives outside formal COP frameworks may prove more consequential than negotiated text, as coalitions of willing nations implement faster transitions without waiting for universal consensus. The fossil fuel transition partnership Brazil launched could establish technology transfer mechanisms, financing structures, and policy coordination, enabling participating nations to accelerate beyond what treaty obligations require. However, effectiveness depends on major emitters joining and maintaining commitments through domestic political transitions, conditions not yet demonstrated.

European Union independence in setting more ambitious timelines than global agreements require provides a potential model for other economic blocs, though replication challenges vary by regional circumstances. EU renewable capacity additions, carbon pricing mechanisms, and border adjustment proposals operate through integrated market structures that smaller economies cannot replicate. Whether similar approaches prove viable in Southeast Asia, Africa, or Latin America depends on regional economic integration levels, financing availability, and political coordination capacities, which differ substantially from European conditions.

The COP30 outcome ultimately preserves diplomatic processes and incremental financial progress while postponing confrontation over fossil fuel transition timelines that would fracture consensus. This preservation of negotiating forums maintains channels for future agreements, but does not accelerate the emissions reductions atmospheric science indicates as necessary. Whether subsequent conferences convert voluntary commitments into binding obligations, or whether parallel coalitions outside COP structures drive actual transition implementation, remains the central question determining climate policy effectiveness through the current decade.