Part IV

- Seals and Caprocks. We humans struggle to keep hydrogen in a specialized vessels made of enforced grade alloy steel, utilizing gas-tight flanges and extra-fine-machined valves – and yet, unsuccessfully: the sneaky thing keeps escaping, which results in substantial losses. (BTW this is the main reason why hydrogen is not really compatible with the long-haul transportation concept – especially via gas pipelines).

Down below the surface, the situation is no much better. According to the “mainstream” beliefs, hydrogen is supposed to be sitting quiet for millions of years beneath the “sealing rocks” just like natural gas.

However, methane happened to have 40% larger molecules (380pm), compared to hydrogen (289pm), although other sources stipulate that hydrogen molecule is just 120pm. This is not the biggest issue here – moreover that hydrogen is known to often migrate as atomic gas (the size of hydrogen atom is 53pm). More importantly, hydrogen is much more chemically aggressive, being the strong reducing agent, while methane is quite neutral. Therefore, hydrogen immediately starts “chewing” on anything it comes into contact with, altering rocks and minerals and turning them into clays, serpentine, and other much softer stuff by means of serpentinization, chloritization, kaolinization and other “-zations”:

- Serpentinization (see Part I):

2Mg2Si04 + Mg2Si2O6 + 4СО + 12Н2 → Mg6Si4O10(ОН)8 + 4СН4

(from Drits et al., 1983).

- Chloritization (see Part II):

5Bio + 3An + 3SiO2(aq) + 4H2O + 6H+= 3Chl + 5Kf + 3Ca2+, and

10Bio + Kln + 7H2O + 10H+= 6Chl + 14SiO2(aq) + 10K+

(from D. Pandit (2014)), etc.

Besides, as you may imagine, those “caprocks” look like anything but “slabs”: they are not monolithic or even homogenous, for that matter. Instead, they are extremely heterogenous due to the so-called facial transitions, which are characteristic both for sedimentary and magmatic formations. Plus, these rocks are repleted with structural dislocations and disconformities such as faults, shear zones, fractures, capillaries, cracks, etc…. and dotted with caverns and voids. All these “impurities” mean more surfaces for hydrogen to “chew” upon, eventually becoming pathways for H2 along its journey upwards.

Even if by chance some rock is relatively monolithic (say, in case of a volcanic flow or an igneous sill), this situation does not persist. Short time passes (geologic time, that is) – and the “slab” gets cracked, sheared, thrusted, weathered from the top and washed-up by hydrothermal fluids from the bottom… the job is done before one may blink their (geochronologic) eye.

This is why the next item seems to be tremendously contradictive:

- Natural Hydrogen Reservoirs. This subject is extremely hot and practical, since everyone seems to be looking for “reservoirs” of natural hydrogen.

Well, we may have bad news for those enthusiasts… please don’t shoot the messenger.

Hydrogen is simply too volatile to reside in porous “gas pays” like methane.

Several companies are actively drilling in the search of natural hydrogen “reservoirs”, others are claiming to have some “secret knowledge” about this topic. However, the lack of practical evidence may be easily explained:

PRESSURIZED RESERVOIRS OF NATURAL HYDROGEN DO NOT EXIST.

Same applies to the traps’ classification taught at Petroleum Engineering 101 – especially to tectonic traps, which in fact become quite opposite for natural hydrogen happily using fault and shear zones’ planar surfaces as migration paths.

We are not trying to say that hydrogen penetrates through the layers of rock like neutrino. Some formations may slow down hydrogen significantly, in the process creating what we call “temporary accumulations” – the closest equivalent of reservoirs, the way we know them for hydrocarbons. These structures may be utilized for natural hydrogen production convenience, just like that famous well at Bourakebougou, Mali.

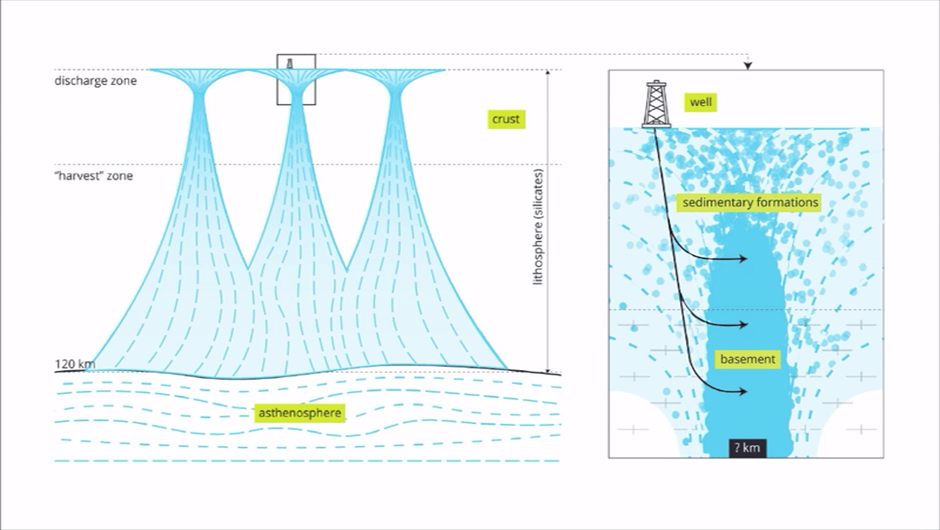

As a result, we have to live with this new reality: It is unrealistic to keep looking for stationary structures where natural hydrogen resides for long periods of time – especially pressurized ones. Instead, the new approach has to be adopted: NATURAL HYDROGEN IS CONVEYED UPWARDS TO THE SURFACE BY MEANS OF (SUB)VERTICAL DYNAMIC STRUCTURES.

This phenomenon was stressed upon by O. Maiga et al. (2023) , stipulating that “hydrogen system is a dynamic system that is recharged while producing”. We take it as an (unwitting) recognition of Dr. V. Larin’s vision of natural hydrogen “chimneys” depicted in the below image.

Concluding on this gloomy subject rather disappointing to some, we may just add that this inability of hydrogen to reside in pressurized reservoirs like methane was explained long time before. It’s not a rocker science: just look at this H2 “thing-y” from the viewpoint of elementary chemistry and molecular physics.

As for the repetitive attempts persistently taken by some of our colleagues to find natural hydrogen “traps” by means of drilling – and unsuccessfully so far… What do they call people who keep doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results?

To be continued…

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Energy News. This content is presented as the author’s analysis based on available information at the time of writing. It should not be considered as representative of Energy News or its editorial stance. Readers are encouraged to consider this as one perspective among many and to form their own opinions based on multiple sources.