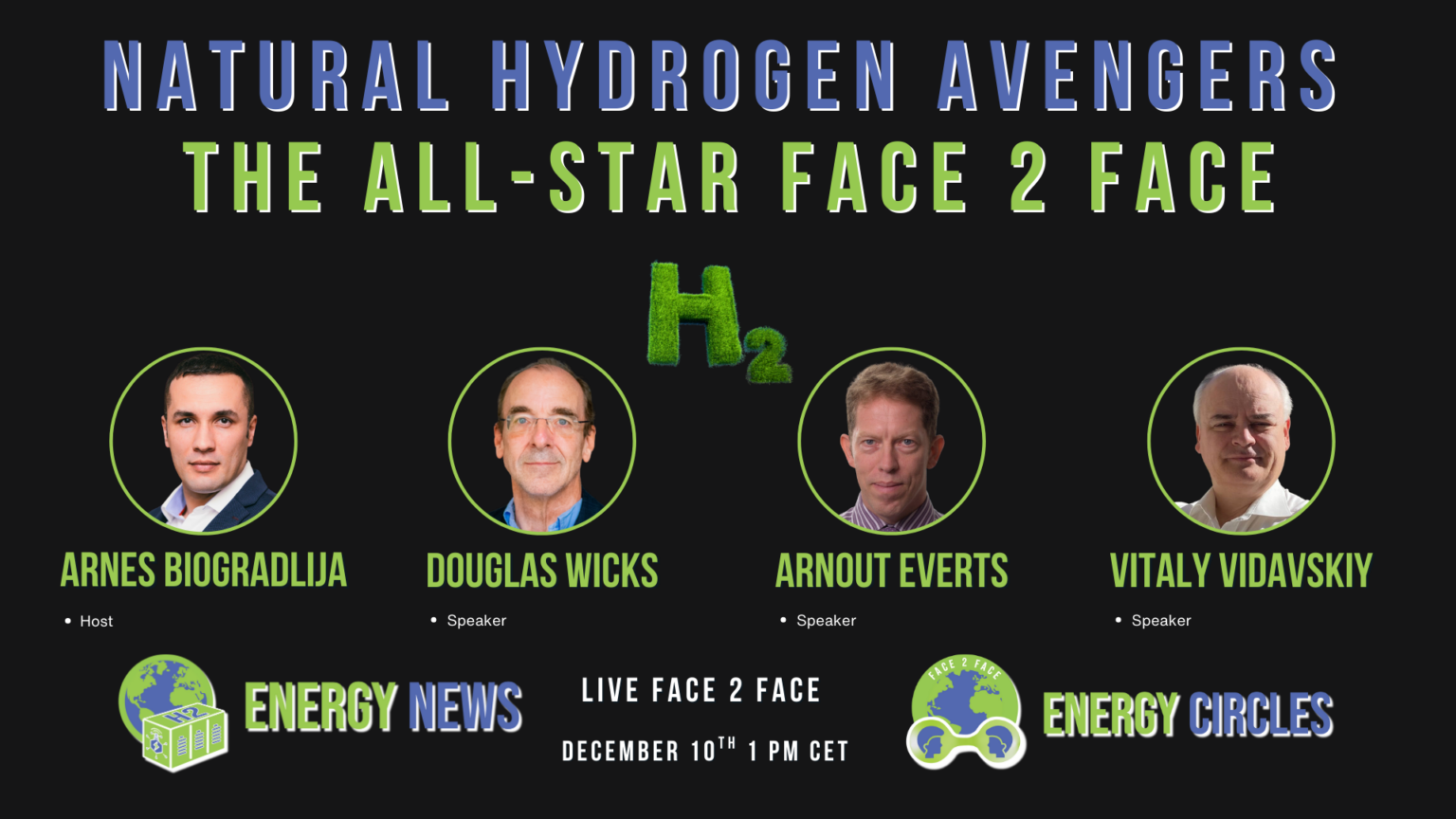

Global hydrogen demand currently consumes close to 100 million tonnes annually for refining and ammonia production, creating a potential market for natural hydrogen if technical and commercial challenges can be resolved. A December panel discussion featuring three experts with divergent perspectives revealed fundamental disagreements about resource assessment methodologies, recovery mechanisms, and timelines to commercialization that expose the nascent sector’s uncertainty.

WATCH THE FACE 2 FACE HERE

Douglas Wicks, former ARPA-E adviser now working with natural hydrogen developers, emphasized engineering solutions and stimulation potential, arguing that subsurface hydrogen generation through serpentinization and other mechanisms can be controlled and enhanced. Arnout Everts, a geoscientist with 35 years in subsurface resource assessment, presented calculations suggesting resource density in seepage systems may prove too low for commercial exploitation, requiring hundreds of square kilometers to supply a single petroleum refinery. Vitaly Vidavskiy, founder of Avalio and early proponent of primordial hydrogen theory, contends that hydrogen originates from Earth’s core hydrides and flows through chimney structures, requiring different exploration approaches than conventional oil and gas methodologies.

The fundamental disagreement centers on recovery mechanisms and resource quantification. Everts applied petroleum engineering principles to calculate that hydrogen dissolved in groundwater at hydrostatic pressure yields resource densities of 1,000 tonnes per square kilometer or less, meaning a petroleum refinery requiring 50,000 tonnes per year for 10 years would need access to 500 square kilometers of resource area. This calculation assumes hydrogen exists primarily in the dissolved phase rather than trapped free gas, a conclusion Everts draws from pressure data showing hydrostatic gradients in wells from Australia and elsewhere rather than gas gradients that would indicate free gas accumulations.

Wicks challenged this framework, arguing that thick sections of ultramafic rock measured in kilometers rather than meters change volumetric calculations substantially compared to oil and gas reservoirs. He referenced recent experimental work by Alexis Templeton in Oman demonstrating hydrogen generation through water injection into dry peridotite, though acknowledged the work remains exploratory. The key engineering question involves whether stimulated systems can produce hydrogen at rates justifying capital investment, a question complicated by equilibrium chemistry considerations that limit hydrogen concentrations in subsurface fluids.

Vidavskiy rejected the premise that natural hydrogen forms pressurized deposits analogous to natural gas fields, arguing that hydrogen’s chemical reactivity and volatility prevent trap formation over geological time. His flux-based model proposes that hydrogen continuously streams from deep sources through focused conduits, requiring identification of high-flux zones rather than trapped accumulations. This conceptual difference drives fundamentally different exploration strategies, with Vidavskiy’s approach emphasizing geophysical detection of vertical flow structures rather than conventional trap geometries.

Industrial hydrogen consumers require a sustained supply over 10 to 15-year contract periods, according to analysis from Oxford Energy Group, with certified reserves backing those commitments. A typical petroleum refinery consuming 50,000 tonnes annually needs 500,000 to 750,000 tonnes of proven reserves to secure financing and offtake agreements. No natural hydrogen project has publicly reported reserve certifications at these scales, though exploration companies have announced hydrogen shows and soil gas anomalies without quantifying recoverable volumes or flow rate sustainability.

The Mali well, often cited as proof of concept, produces hydrogen from a borehole drilled in 1987, but production rates and sustainability metrics remain poorly documented in public sources. Projects in Nebraska, Australia, and elsewhere have demonstrated hydrogen presence through drilling without establishing commercial viability. The gap between hydrogen detection and commercial production reflects challenges common to unconventional resource development, where resource existence differs fundamentally from economic recoverability.

Productivity requirements compound resource density challenges. A single well producing 1,000 tonnes per year at a refinery requiring 50,000 tonnes annually necessitates 50 wells, while a productivity of 10,000 tonnes per well reduces the requirements to five wells. Well productivity depends on reservoir permeability, pressure support mechanisms, and hydrogen saturation levels, parameters that remain poorly characterized in natural hydrogen systems. The relative permeability behavior of hydrogen-water systems at low hydrogen saturations creates production challenges, as water remains the dominant mobile phase unless free gas saturations exceed critical thresholds.

Monetization of initial production emerged as a critical bottleneck, with all three experts acknowledging that industrial-scale offtakers will not commit to unproven resources. Wicks emphasized the U.S. merchant hydrogen market served by 2,500 compressed gas tube trailers, suggesting that mobile purification and compression systems could enable early-stage production monetization without requiring pipeline infrastructure or large-scale industrial customers. This approach parallels tight gas development, where distributed production feeding existing markets preceded large-scale field development.

The timeline comparison to tight gas development proved instructive. Fundamental research in the 1980s by the U.S. National Energy Technology Laboratory developed horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies. Mitchell Energy conducted field trials throughout the 1990s before achieving economic flow rates in 1997, with commercial production scaling over the subsequent decade. This 30-year trajectory from concept to commercial scale provides context for natural hydrogen timelines, though proponents argue that modern subsurface technologies and data analysis could compress development periods.

Stimulated hydrogen production through water injection into ultramafic rocks generated particular debate. Wicks noted that U.S. hydraulic fracturing in tight formations now achieves fracture propagation measured in kilometers rather than meters, though Vidavskiy and Everts questioned whether fracture geometries in crystalline rocks would support sufficient reaction surface area for commercial hydrogen generation. The planar fracture geometry typical in crystalline rocks differs from the fracture network complexity achieved in sedimentary formations, potentially limiting reactive surface area relative to stimulation costs.

Exploration methodology disagreements reflect different conceptual models. Companies drilling adjacent to legacy wells with historical hydrogen show follow conventional oil and gas approaches of exploiting known occurrences. Everts criticized this strategy as lacking proper prospect maturation, arguing that successful petroleum exploration requires systematic play analysis identifying source rocks, reservoirs, seals, and migration pathways before drilling. He contended that natural hydrogen exploration largely bypasses this analytical framework, instead drilling proximate to historical anomalies without demonstrating an understanding of hydrogen systems.

Vidavskiy’s proprietary soil sampling and geophysical methods claim to identify vertical flux pathways that conventional approaches miss, though the methodology details remain confidential for competitive reasons. This creates verification challenges common in early-stage resource sectors where technical differentiation provides a competitive advantage but limits independent assessment of claimed capabilities. The tension between proprietary methods and scientific transparency affects sector credibility as investors evaluate competing technical narratives.

Quebec’s activity concentration illustrates market dynamics, with QIMC securing land positions based on soil gas surveys, followed by multiple companies acquiring adjacent acreage. Vidavskiy distinguished QIMC’s flux-based exploration from competitors pursuing land-grabbing strategies without comparable technical foundations, though external validation of these distinctions remains limited given sparse public data. The land rush pattern mirrors early stages of other resource plays where initial discoveries trigger speculative positioning before technical understanding matures.

Cost estimates for natural hydrogen production vary widely and often exclude critical elements beyond well drilling. Everts noted that published cost analyses typically omit completion design, surface facilities, pipeline infrastructure, water disposal systems, and gas processing to achieve required purity specifications. These omitted costs proved decisive in tight gas economics, where drilling represented a fraction of total field development expenditure. Natural hydrogen faces similar or greater facility costs given hydrogen’s material compatibility challenges and purity requirements for end-use applications.

The sector confronts a classic catch-22 where resource quantification requires production testing, but financing production infrastructure demands certified reserves. This circular dependency afflicted tight gas development until risk-tolerant operators demonstrated commercial viability, enabling broader industry participation. Natural hydrogen lacks government research funding comparable to the Department of Energy’s unconventional gas programs, placing commercialization burden on venture capital and philanthropic sources, including Renaissance Philanthropy’s recently announced challenge fund.

Pressure data from natural hydrogen wells consistently show hydrostatic gradients rather than gas gradients, according to Everts’ analysis of publicly available information. This observation suggests hydrogen exists primarily in the dissolved phase with potentially small residual gas saturations, fundamentally different from natural gas fields where the gas phase dominates pore space. The dissolved gas environment creates production challenges analogous to solution gas drive mechanisms in oil reservoirs, where productivity depends on liberating dissolved gas through pressure reduction while managing water production.

Everts estimated that commercial natural hydrogen production at meaningful scales would not occur by 2030 even if exploration proves successful, citing the extended appraisal and pilot production phases required to characterize resource extent and productivity. This timeline estimate conflicts with some industry projections suggesting near-term commercial production, highlighting the disconnect between promotional timelines and technical realities that often characterize early-stage resource sectors.

The comparison to renewable hydrogen costs will ultimately determine market positioning. Electrolysis using renewable power has established supply chains, understood economics, and scalability potential despite current high costs. Natural hydrogen must demonstrate not only technical viability but also cost competitiveness, including all production, purification, and delivery expenses. Current cost estimates for natural hydrogen range widely and depend heavily on assumptions about well productivity, resource density, and facility requirements that lack empirical validation.

Hydrogen purity requirements vary by end use, with fuel cells requiring 99.97% purity while ammonia synthesis tolerates lower specifications. Natural hydrogen from subsurface sources typically contains nitrogen, carbon dioxide, methane, and other components requiring separation. The separation costs scale with contaminant concentrations and desired purity levels, potentially consuming significant portions of production value, particularly for small-scale operations where equipment utilization rates remain low.

The discussion revealed that while Earth naturally produces hydrogen through multiple mechanisms, the engineering challenge involves concentrating that production into economically recoverable flows at the surface. Whether serpentinization, radiolysis, primordial degassing, or other mechanisms dominate remains disputed, though all participants agreed that hydrogen generation occurs. The critical question involves recovery efficiency and whether natural or stimulated systems can achieve productivity justifying development costs.

Several factors differentiate natural hydrogen from oil and gas development beyond the obvious chemical differences. Hydrogen’s low viscosity and density affect fluid flow behavior, while its reactivity creates material compatibility challenges in wellbores and surface equipment. The lack of existing hydrogen pipeline infrastructure limits market access compared to natural gas, which benefits from extensive transmission networks. These technical and infrastructure differences compound the resource assessment uncertainties to create compounded risk profiles that affect investment decisions.

The experts achieved consensus on several points despite their different perspectives. All agreed that claims require field validation through drilling and production testing. All acknowledged that monetizing initial production presents commercial challenges given the absence of proximate large-scale demand and the costs of compression, purification, and transport. All recognized that the sector needs improved data sharing and standardized assessment methodologies to progress beyond speculative positioning toward systematic resource development.