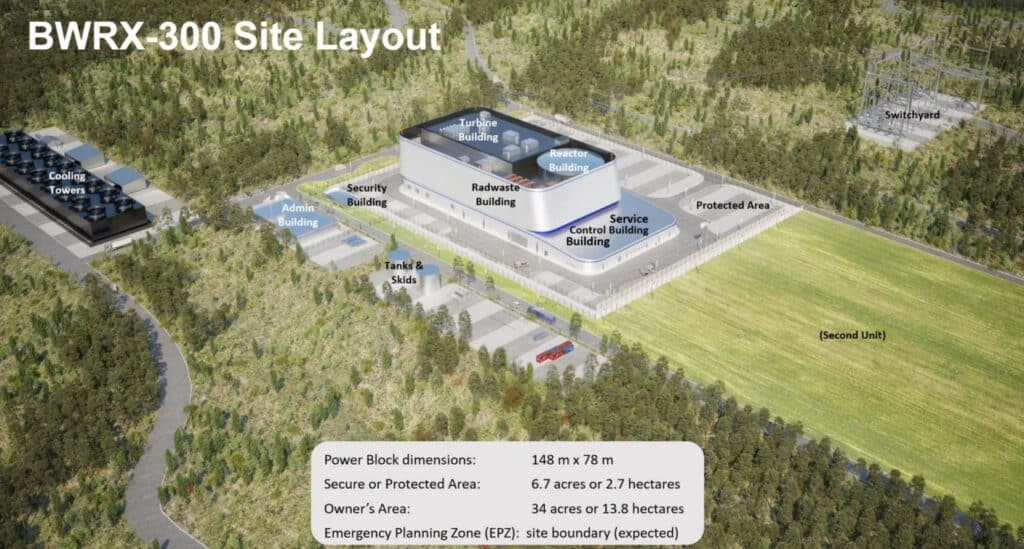

The U.S. Department of Energy has allocated $400 million to the Tennessee Valley Authority for the deployment of GE Vernova Hitachi Nuclear Energy’s BWRX-300 small modular reactor at the Clinch River Site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The funding, announced December 2, 2025, targets commercial operation in the early 2030s, positioning the project as the nation’s first operational commercial SMR if regulatory and construction timelines hold.

The grant flows through DOE’s Generation III+ SMR program and follows TVA’s May 2025 construction permit application to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. GE Vernova CEO Scott Strazik characterizes the BWRX-300 as the only commercial SMR technology currently under construction in the Western world, though this claim requires examination against competing designs and their development status.

Technology Positioning and Competitive Landscape

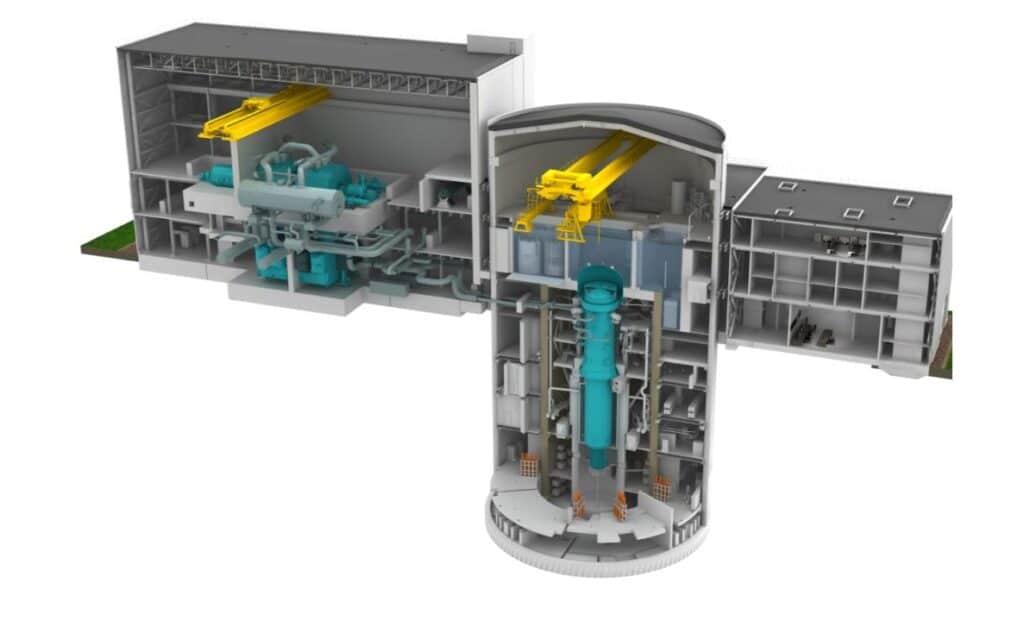

The BWRX-300 employs a boiling water reactor design scaled to approximately 300 megawatts electric output, roughly one-third the capacity of conventional large nuclear units. GE Hitachi’s design builds on proven boiling water reactor technology used in multiple operating plants globally, which the company presents as a de-risking factor compared to novel reactor concepts requiring more extensive demonstration.

Strazik’s assertion about Western SMR construction warrants scrutiny. While the BWRX-300 may lead in terms of construction permit applications filed with U.S. regulators, several competing designs have achieved various stages of regulatory review or early-stage development internationally. NuScale Power’s design received NRC certification in 2020, though no construction has commenced. TerraPower’s Natrium reactor broke ground in Wyoming, though it incorporates sodium cooling rather than water, placing it in a different technical category.

The distinction between construction activity, regulatory progress, and commercial viability matters significantly. A construction permit application under NRC review differs substantially from actual construction underway, and neither guarantees successful commissioning or economic operation. Nuclear project histories demonstrate consistent patterns of schedule delays and cost overruns that affect even proven technologies.

Federal Funding Strategy and Public-Private Risk Allocation

The $400 million grant represents a significant federal commitment to SMR commercialization, yet it covers only a portion of the total project costs. TVA has not disclosed complete project economics, including total capital requirements, anticipated capacity factors, or projected levelized costs of electricity. These omissions prevent meaningful assessment of whether the technology achieves cost competitiveness against alternatives or merely transfers financial risk from utilities to taxpayers.

DOE’s Generation III+ SMR program structure requires utility-led coalitions partnering with technology vendors. TVA’s application involved multiple utility and industry partners beyond GE Vernova Hitachi, suggesting some level of sector confidence in the design. However, participation in a grant application differs from commitment to replicate the technology at participant utilities’ own sites with their own capital.

The emphasis on public-private partnerships and energy security in DOE and GE Vernova statements indicates the federal government views nuclear capacity as strategic infrastructure warranting subsidy beyond what market economics alone would support. This framing sidesteps questions about whether $400 million in federal funds allocated to nuclear deployment represents optimal climate mitigation spending compared to alternatives like transmission expansion, long-duration storage, or renewable capacity.

Regulatory Timeline and Construction Risks

TVA’s May 2025 construction permit application initiates a multi-year NRC review process with uncertain duration. The regulatory body must evaluate site suitability, design safety, emergency planning, and environmental impacts before authorizing construction. Even with design certification completed separately, construction permit reviews typically extend multiple years, and NRC can require design modifications or additional safety demonstrations.

The early 2030s commercial operation target assumes regulatory approval, successful construction execution, and commissioning without major complications. Nuclear construction projects consistently exceed initial schedules. The Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia, the only nuclear units completed in the U.S. in recent decades, experienced years of delays and billions in cost overruns despite using an NRC-certified Westinghouse AP1000 design theoretically simplified for faster deployment.

SMR proponents argue that smaller unit size, modular construction, and factory fabrication of major components will avoid the scheduling and cost problems that plague large nuclear projects. These claims remain unproven at a commercial scale in Western markets. The BWRX-300 at Clinch River will test whether module fabrication and reduced construction scope translate to improved project execution or whether nuclear-specific regulatory, quality assurance, and skilled labor constraints override scale benefits.

Supply Chain and Manufacturing Capacity

GE Vernova and DOE statements emphasize supply chain strengthening as a grant objective. U.S. nuclear manufacturing capacity has atrophied over decades without domestic new-build activity, creating dependencies on international suppliers and raising questions about fabrication quality and security of supply for critical components.

Reviving domestic nuclear supply chains requires sustained order flow, not single projects. The BWRX-300 deployment creates limited manufacturing demand unless additional units follow. TVA has not committed to multiple units, and no other U.S. utilities have announced firm BWRX-300 purchase agreements, though Ontario Power Generation in Canada is pursuing the same design.

The coalition structure of the grant application might indicate broader utility interest, but interest expressed in a funding proposal differs from capital commitment. Utilities face regulatory and shareholder scrutiny on major capital projects, particularly nuclear, given historical cost performance. Without firm purchase commitments from multiple buyers, equipment manufacturers face chicken-and-egg dynamics where they cannot justify capacity investments without orders, but utilities hesitate to order without demonstrated manufacturing capability and cost certainty.

Market Context and Generation Mix Evolution

TVA operates in a service territory with substantial existing hydroelectric and nuclear capacity, plus growing solar deployment. The utility’s interest in additional nuclear capacity reflects base load preferences and carbon reduction mandates, though natural gas combined cycle plants with carbon capture, offshore wind, and battery storage represent alternative paths to similar objectives.

The early 2030s timeframe for BWRX-300 commissioning places it in competition with renewable and storage technologies that will have experienced another seven to eight years of cost declines and efficiency improvements. Solar, wind, and battery costs have fallen consistently for decades, while nuclear costs have risen. Whether SMRs reverse nuclear cost trends or merely moderate them relative to large reactors remains the central unresolved question for the technology’s commercial viability.

Federal funding reduces TVA’s direct financial exposure but does not eliminate construction, operational, or economic risks. If the Clinch River BWRX-300 experiences significant delays or cost overruns, it could dampen rather than accelerate subsequent SMR deployment regardless of DOE’s intentions. The project functions as both a demonstration and a test case, with outcomes likely to influence utility appetite for nuclear investments beyond rhetorical support.